Why Microsoft Could Get The Xbox Series X Price Down To $399 – Forbes

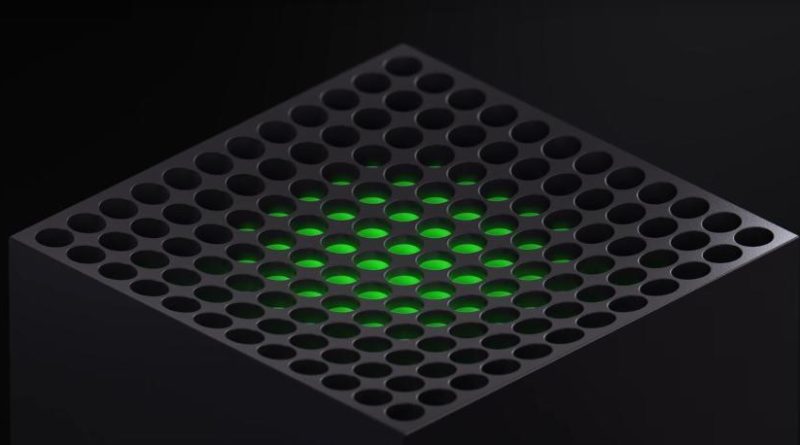

Xbox Series X

Credit: Microsoft

We’ve seen Microsoft’s Xbox Series X, now. Shocking nobody, it’s going to be a big black rectangle, even if it’s being shown standing up in the first promotional images. And while seeing the thing or knowing the name doesn’t tell us a whole lot more than we already know about what the box actually is, it’s fueled speculation about arguably the biggest remaining question mark: the price. Power is one thing, but at the end of the day power is only a function of price: you can make a ridiculously powerful console, but people won’t buy it if it costs too much.

People have been throwing the number $600 around based on the theoretical cost of manufacturing inferred from commercially available components. Something similar happened with the PS5 over the summer, when people were throwing around $800 after a piece of obvious analyst hyperbole. Both are most likely wrong, and there’s a good reason why.

It’s pretty simple, really. Consoles have traditionally been either loss leaders for the companies that make them or pretty close to being loss leaders: manufacturers either don’t make a profit off of them or make a pretty moderate profit, hoping to make the bulk of their money off of games and licensing. That’s always been true, and it’s helped keep the price of consoles down at the outset.

It’s even more true now, however. Over the course of last generation subscription services like Xbox Live Gold and PlayStation Plus became more and more widespread: earlier in the year, PlayStation Plus had an attach rate of about 40 percent. Microsoft also has Game Pass, giving the company another way to ensure stable monthly income off of any subscribers. In addition to that, the increasing rise of digital purchases of both games and in-game items means that platform holders get to take a retailer’s cut of a game sale that would have gone to a company like GameStop otherwise. Basically, console manufacturers/platform holders have more opportunity to make money after the initial console sale than ever before, and that means it can continue to offer consoles at prices we’re used to even as manufacturing costs go up.

The price of your modern, connected console is not just the initial purchase price. It’s also the price of the service subscription that it takes to keep the thing running as a feature complete package, and both Sony and Microsoft are figuring that into the sticker price.

My somewhat outlandish guess is that this machine is going to come in at a surprisingly-low $399. That would almost definitely mean that Microsoft would be selling these at a loss, but I expect that will be happening regardless.

Let’s call $399 the stretch goal: it’s certainly not going below that. $499 is a strong possibility as well, but Microsoft lost badly with a $499 console last generation and doesn’t want a repeat performance. Games are not nearly as important to Microsoft’s bottom line as they are to Sony’s, and so it’s easy to imagine that the tech giant could use its considerable muscle to bring the price down and gain an advantage in the console war after an underperforming generation.

The wild card here would be if Microsoft chooses to release two consoles at launch: the premium series X and one other that we haven’t heard about yet. There’s no playbook on that kind of a move, but it would support the idea of selling the Series X at a higher price with a lower cost box to attract the budget conscious.